Obama and Republicans talk bipartisanship, but most of the action is in the other direction

By Charles Babington, APTuesday, February 9, 2010

Despite all the nice talk, partisanship reigns

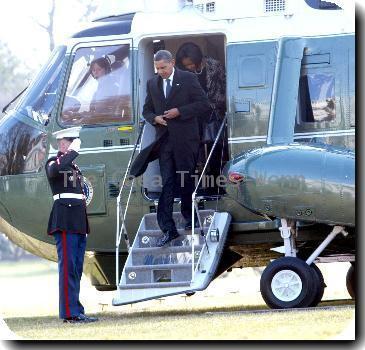

WASHINGTON — Partisanship is reaching new heights in Washington, even as President Barack Obama makes almost daily pleas to get along. He’s scheduled a bipartisan health care summit, and just Tuesday he hosted GOP leaders at the White House for the first time in two months.

But he often undercuts his overtures with his own jabs at Republicans. And there’s little indication the GOP is taking his comments as anything but political.

Both sides’ stances might be summed up this way: We’re ready to cooperate right now. All you need to do is go along with what we want.

On Capitol Hill, the minority Republicans routinely require a super-majority (60 votes out of 100) to move Senate bills. And only one GOP lawmaker, a House member, voted for the landmark health care bills approved separately by the House and Senate in December. The Democrats, meanwhile, wrote the House and Senate health care bills with virtually no input from Republicans.

How has this come about? The contributing factors have been accelerating and converging for years: Gerrymandered House districts. Political realignments that drive Democrats from the South and Republicans from the Northeast.

And perhaps most of all: greater mobilization by both parties’ ideological wings, who punish those who dare cooperate with the other side.

House and Senate members once saw the opposition party as the adversary, but now they consider it the outright enemy, said Norman J. Ornstein, a congressional scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.

Americans “are dividing into tribes more than we did before,” he said. Voters have driven virtually all liberals out of the Republican Party and all conservatives from the Democratic Party, eliminating a political dynamic that helped enact major legislation such as civil rights and Medicare in earlier decades.

Obama made a multi-pronged appeal for bipartisanship Tuesday. He hosted Republican congressional leaders at a meeting on jobs, then held an unannounced news conference to ask for greater Democratic-GOP accord on at least a half dozen issues.

But any doubts that bare-knuckled partisanship still grips Washington were diminished when Republican leaders stepped outside the White House and denounced Obama’s health care plan, even suggesting they might not attend his Feb. 25 summit.

Tuesday was a perfect example of high-minded appeals for cross-party cooperation being quickly undermined by barbs. Obama and Republican leaders couldn’t even agree on a definition of bipartisanship.

“Bipartisan cannot mean simply that Democrats give up everything that they believe in, find the handful of things that Republicans have been advocating for, and we do those things, and then we have bipartisanship,” Obama told reporters. “There’s got to be some give and take.”

Two hours earlier, House Minority Leader John Boehner had stood outside the White House and openly questioned whether Obama’s bipartisan health care summit will have any value. He and Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell said Obama first must scrap the Democrats’ bills; Obama says no.

That followed Monday’s letter from Boehner and House Republican Whip Eric Cantor in which they told the president: “‘Bipartisanship’ is not writing proposals of your own behind closed doors, then unveiling them and demanding Republican support.”

Other examples, just on Tuesday, of how difficult bipartisanship will be:

— Obama said he would work with Republicans on energy in areas such as nuclear power, clean coal technology and oil drilling. But when he noted that McConnell supports the ideas, he added a dig: “Well, of course he likes that. That’s part of the Republican agenda.”

— Obama offered his strongest rebuke yet of Republicans for holding up his federal appointments, saying the Senate had turned “advice and consent” into “delay and obstruct.” He threatened to start installing appointees when Congress is in recess.

— Obama insisted that he wanted substantive talks, not theater, at the health care summit. The Republican National Committee promptly accused him of using the meeting as “political theater to attack Republicans.”

— Boehner labeled an op-ed column by an Obama administration official a “cheap, irresponsible political smear.” Deputy National Security Adviser John Brennan had written in USA Today that “politically motivated criticism” of administration policies “only serve the goals of al-Qaida.”

Throughout the day, both sides accused the other of wanting to take without giving. Despite all the calls for brotherhood, no one offered a new map for how Congress might resolve impasses over energy, debt reduction, health care and immigration, let alone the looming problems with Social Security and Medicare that have gone unaddressed for years.

Partisanship’s long rise has left milestones along the way. Conservatives punished President George H.W. Bush for working with Democrats and breaking his “read my lips” pledge against new taxes. No House Republicans voted for President Bill Clinton’s high-profile 1993 economics package.

But it seems worse now, and there are plenty of reasons.

House members have been shoved farther to the political left and right by one of the few major agreements between the two parties: to protect incumbents every 10 years by drawing safe districts for them, meaning more liberal or conservative districts.

Highly motivated activist groups — such as Moveon.org on the left, and the Club for Growth and the “tea party” on the right — are forcing senators to worry about losing primary elections, which often are low-turnout affairs dominated by ideological voters. Many lawmakers say that dynamic accounts for sharp turns to the right lately by Republican Sens. John McCain of Arizona, Charles Grassley of Iowa and Bob Bennett of Utah, all of whom were known to cross party lines at times. Grassley’s actions last year particularly hurt efforts to craft a bipartisan health bill.

Former Republican Sen. Arlen Specter of Pennsylvania switched to the Democratic Party, convinced he could not survive a GOP primary challenge from the right this year.

It’s still possible, of course, that partisanship might ease a bit in coming weeks and months, perhaps lighting a path for enactment of a major health care bill.

After the White House meeting, Boehner, McConnell and others returned to a Capitol so surrounded with ice and snow that House leaders canceled votes for the rest of the week. Maybe the break will cool the partisan rhetoric. History suggests otherwise.

Associated Press writer Ben Feller contributed to this report.

Tags: Barack Obama, Bill Clinton, District Of Columbia, Geography, Government Programs, Government Regulations, Government-funded Health Insurance, Health Care Reform, Industry Regulation, North America, Occasions, Parties, Political Issues, Political Organizations, Political Parties, United States, Washington