‘It takes action’: Tea party backers explain their journey from enraged to engaged

By Pauline Arrillaga, APSaturday, June 19, 2010

Enraged to engaged: Tea party backers explain why

YUCCA VALLEY, Calif. — Bill Warner is hardly a naive man. He ran his own engineering firm for three decades, and sold the assets just before the economy tanked. He built his dream home on a majestic hill abutting a national park, back when the housing market was steady. While some neighbors have since been foreclosed upon, Warner is resurfacing his flagstone deck.

And so he understands, quite clearly, that in the world of politics, his little group — officially, the Lincoln Club of the Morongo Basin — is but a molecule in the figurative drop in the bucket of power and influence.

Its stated purpose is “to promote, educate and advance conservative principles of fiscal responsibility, small limited government, free enterprise, the rule of law, private property rights, and the preservation and protection of individual liberty.” The organization has, to date, some 25 members and has raised $10,000.

Moveon.org or FreedomWorks it isn’t. But to Warner, it’s no less substantial.

“It’s our way of doing what we can do,” he says.

Warner is 65, soft-spoken, the kind who asks questions before making decisions. Think Bob Newhart without all the wisecracks. He doesn’t consider himself a rabble-rouser or “tea party-er.”

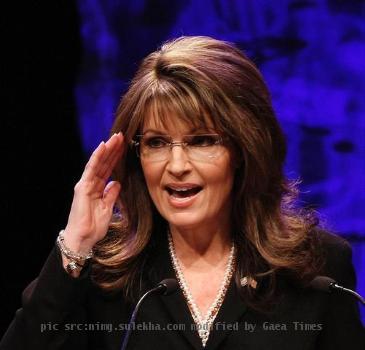

Yet this past March, Warner packed up his motorhome and drove almost 200 miles with his wife, Pat, and dogs Eddie and Peanut to a dirt lot next to a gravel pit in Searchlight, Nev. There he sat one Saturday, bundled up in a blustery wind, with thousands of others at a tea party rally that was dubbed the Woodstock of conservatism.

There were, as his friend put it, some “wackadoos” among the masses: The Barrel Man, who wore only, well, a barrel and a hat. The guy dressed like Jesus. The fellow with the “Texas It Is Time To Secede” placard.

There were also plenty of people just like Warner, who held a coffee mug instead of a sign.

Concerned Americans trying to find their voices, and a way to channel their disgust. For some of them, all that anger has now turned to action.

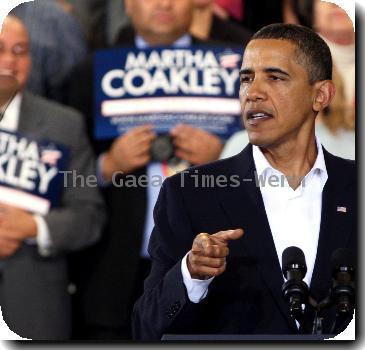

It is the kind of action that helped tea party favorite Sharron Angle come from behind in the polls to capture the Republican nomination for U.S. Senate in Nevada, challenging Majority Leader Harry Reid. And the kind that helped tea party darlings Raul Labrador in Idaho and Todd Lally in Kentucky win their Republican congressional primaries. And that helped libertarian favorite Rand Paul beat out a Republican establishment candidate in Kentucky’s Senate primary. And has mainstream Republican Charlie Crist now running as an independent in Florida’s Senate race.

In Yucca Valley, that action comes from the likes of Bill Warner and a new Lincoln Club.

In Bullhead City, Ariz., it comes in the form of an ex-PR agent who runs the Republican women’s club, volunteers as a precinct committee person and holds candidate meet-and-greets to help get out the vote.

In Las Vegas, it’s an Internet marketer and his friend, a blogger, working from a rented condo to oust Reid and other incumbents.

These four were all in Searchlight that Saturday in March. They’ve heard, time and again, the characterizations in the news media, from some Democrats and, in certain cases, from their own friends and relatives — about how “those tea party-ers” are just angry voters venting about economic hard times, or they’re confused, uneducated and easily influenced, or they’re extremists, or, worst of all, they’re racists.

Months after Searchlight and all the rallies that came before and after, plenty of questions remain about just what the tea party is, whether it can endure and how much influence it will have on elections this year and in years to come.

Part of the answer is this: In communities across the land, citizens-turned-activists are digging in in different ways — whether as part of some official tea party group or something else — to wield whatever power and influence they’re able to muster over this thing called democracy.

To hear what motivates them is to begin to understand what’s going on in American politics in 2010.

Really, in America itself.

Her accent screams Long Island and she seems better suited for an episode of “The Real Housewives of New York City” than the Chaparral Country Club in Bullhead City. Yet here she is, Hildy Angius, holding court with three older gentlemen who’ve just finished a round of golf in this retirement community in the far northwest corner of Arizona.

Her hand is filled with fliers for a mixer sponsored by the Colorado River Republican Women, the organization she heads, and she’s trying to convince the men to show. “It’s more like a voter registration. A lot of elected people. It gives you a chance to go out and yell at them if you have any problems or questions,” she says.

Turns out they, like Angius, have plenty they’d like to yell about. One of the golfers, between sips of a stiff drink, asks about the country he loves: “Why are we in such dire straits?”

“Years of neglect,” says Angius.

“Democrats!” another golfer exclaims.

The guy with the drink chimes back in: “How about debt?”

Spotting an opening, Angius launches into the speech she delivers these days to friends and strangers alike, whether at tea party rallies, the local coffee shop or on Facebook. The upshot: Don’t gripe, do something. Vote. Volunteer. Knock on doors.

Do, in essence, what she’s now doing: Whatever it takes to move the Republican Party, and the government, to the right.

Angius says she’s always had a big mouth. She once appeared on “Oprah” to debate a Generation Xer on behalf of baby boomers. An avid Rush Limbaugh fan, she’s called in to his show on any number of occasions.

Still, she acknowledges she did little more than complain until September 2008, when she realized Barack Obama was likely to win the presidency, bringing to office a far too liberal agenda that would mean the kind of changes Angius vehemently opposes. Never before a “joiner,” she went online, learned about the Colorado River Republican Women, went to a meeting and found an outlet for her dismay.

This past January, she was elected president of the club. Soon after, she volunteered as a precinct committee person in her voting district.

At 51 and retired, she now spends her days organizing events featuring Republican candidates, getting ready to go door-to-door to get voters to the polls for Arizona’s August primary and writing newsletters that help promote tea party protests, town hall meetings and conservative initiatives such as the state’s new immigration law that will require police to verify people’s immigration status if there is “reasonable suspicion” they are in the country illegally.

It’s an appropriate gig for a former marketing and public relations specialist. Angius knows how to sell something, and nowadays her pitch is a strong, anti-incumbent, very tea party sort of line — a byproduct, perhaps, of the big rallies she’s attended in Searchlight and Washington, D.C.

But the tea party didn’t shape Angius; she’s not even a member of any local “chapters” in Arizona. Her views developed long before, growing up on Long Island, the youngest of three children in, as she describes it, an upper-middle class Jewish — and politically conservative — home.

Her father, Ed Linn, was a magazine writer and author, who profiled everyone from baseball great Sandy Koufax and Teamster leader Jimmy Hoffa to Jack Kennedy and Richard Nixon. He was also a product of the Great Depression who instilled in his daughter the core tenets of conservatism: hard work, self-reliance, small government and low taxes. Political discussions were customary in the Linn house, where newspapers covered the tables and, later, the voice of conservative talk radio pioneer Bob Grant filled the air.

“My father was the most principled man I’ve ever met in my life,” says Angius. “He was my hero.”

He demonstrated how to not only stand up for one’s beliefs but how to defend them, a talent that came in handy for a girl who grew up in a predominantly Democratic neighborhood, attended state university in Albany with mainly liberal friends, worked in Manhattan doing public relations for the movie channel Showtime and whose childhood chums, not to mention a lot of relatives, are mostly Democrats.

“There was never anyone on my side, so I always had to stand up for what I believed — no matter what it cost. That’s what I learned at home. You know this thing about ‘moderate?’ There is no virtue in moderation,” she said, paraphrasing the iconic conservative, Barry Goldwater of Arizona.

What finally pushed Angius to action was Obama, and it infuriates her when those who can’t understand that suggest race is somehow the motivation. That may be true for some, she acknowledges. For her, it comes down to the competing and vastly divergent ideologies of the left vs. the right, and a feeling that American conservatives have been marginalized for years — throughout even the presidency of George W. Bush.

Bush, she says, “spent like a drunken sailor. He reached across the aisle. We weren’t happy with the taxes. We weren’t happy with his policy on illegal immigration. So, by the time he left, he was not very popular among conservatives. Because he was not conservative.”

Then came the worst-case scenario for someone like Angius: Obama and a Democratic-controlled Congress. More financial bailouts. And the stimulus bill. And health care. And now talk of taking on immigration reform. Ask her to explain what the anger and “fear” and anti-incumbent fervor are all about, and she talks about a feeling that something is just “wrong.”

“This is not the direction that the country is supposed to be going,” she says. “Things are changing at warp speed in a way that’s not going to be good.”

And so, she says, people are getting more involved.

Angius’ way is to work to change things from within the Republican Party, and inside the voting booth. In May, she drove more than 200 miles to Phoenix to join about 70 others at a Republican National Committee program that teaches everyday advocates how to get the party’s message out. It was called, “Say It Loud.”

Angius is certainly good at that. As she goes around Bullhead City promoting various events, she talks and talks. About how the political pendulum swung too far to the left with Obama’s election. About getting rid of Democratic congressional leaders Reid and Nancy Pelosi. About taking aim at incumbents, Republicans included, who simply aren’t conservative enough. For her, that includes Arizona’s longtime GOP senator, John McCain.

When folks around town ask her whom she plans to support in that all-important Senate primary on Aug. 24, she first explains that her views are her own (her women’s club doesn’t endorse candidates) and then she tells them, in all likelihood, McCain’s more conservative opponent, J.D. Hayworth.

“I want McCain to lose for the symbolism,” says Angius. “He’s like the ring on the merry-go-round. If we can get that, the tea parties have won.”

This is how momentum — a “movement,” even — can grow. One person, on the ground, talking to others, inspiring action and influencing votes.

Ask her if she’s radical and Angius smiles and sasses back, “I hope so. Radicals get things done.” Then, she reconsiders and says: “I just feel strongly about something.”

The day she passed out fliers for her mixer, Angius went from the golf club to the Mohave Steakhouse, where the 20-something woman behind the hostess stand promised to ask her boss about posting the notice and then allowed, unprovoked, “Yeah, I went to the Palin thing,” meaning the Searchlight tea party rally, where Sarah Palin urged the crowd to action.

At the Silly Cactus T-shirt store, the guy manning the register gave a quick “Absolutely” when Angius asked if he’d hang up one of her bulletins. A photo displayed on the counter beside him showed off the scene at the Sept. 12, 2009, tea party rally in Washington, D.C.

Angius, apparently, isn’t the only one here feeling “strongly.”

If there is a father of the tea party, some would say Eric Odom is that man. Others would insist the tea party has no one forebear or leader, and even Odom himself prefers the word “organizer.” But how many organizers do this: This past March, Odom picked up his life in Chicago, left behind most of his belongings, put on hold a career as an Internet consultant and moved with his fiancee and a blogger friend into a three-bedroom apartment a few miles from the Las Vegas Strip.

There, in a cramped dining space turned “war room,” the 30-year-old helps direct the assault that is feeding the nation’s antiestablishment frenzy and helping to take out incumbents in primaries across the country.

When those like Angius and Warner ponder how to go from exasperated to engaged, Odom stands at the ready with an e-mail or a Tweet — and an answer.

Six years ago, Odom was a college student in Reno, Nev., studying graphic communications and quickly becoming an expert in the art of using the Internet to communicate, whether by designing Web pages, buying domain names or doing search engine optimization to help funnel traffic to certain websites or blogs.

He wasn’t politically involved. In fact, he says he didn’t even vote.

But in 2004, when George W. Bush was running for re-election, Odom started using his Internet skills to do some contract work. And he started noticing how much of his paycheck went to taxes. Illegal immigration was a growing problem in Nevada, and he began to take notice of that, too. He also believed Bush’s Democratic opponent, John Kerry, was a “buffoon.”

So one day Odom walked into the Washoe County Republican Party’s headquarters to offer to revamp its website to make it more user-friendly and help attract younger voters. It was his way of, well, taking some action. But when he went back to show the Republicans what he had done, he says leaders rejected his work because it wasn’t “run through their process.”

In almost an instant, Odom went from apolitical to antiestablishment activist.

He launched his website anyway, then started a conservative political action committee and was quoted in the Reno Gazette Journal as saying the county Republicans were as “‘effective as a lead balloon’ at engaging people in politics.” Soon, he was working for conservative candidates who didn’t have the party’s backing and, when he saw them lose, was inspired to fight on.

By 2006, Odom had a conservative blog and was organizing citizens to “slam” Nevada lawmakers with phone calls over legislation they opposed. By 2008, he had moved to Chicago and was using his Internet skills to reach out to activists on behalf of the Sam Adams Alliance, a nonprofit advancing free-market principles. Then came the “Dontgo Movement” to push for an end to bans on offshore drilling.

And finally, in February 2009, Odom, like so many others, was watching when CNBC reporter Rick Santelli stood on the floor of the Chicago Board of Trade, ranting about stimulus money and the mortgage crisis and calling on capitalists to converge at Lake Michigan for a “Chicago tea party.”

In 24 hours, Odom had a website up to help organize just that, and his tea party career took off.

The culmination of all of that is the new political action committee he heads, Liberty First, and its offshoots, TaxDayTeaParty.com and The Patriot Caucus, which he describes as a coalition of tea party activists and organizers who want to “engage the movement in electoral activism.”

And so he spends his days in front of a computer in that Las Vegas condo war room, under a banner that reads “Silent Majority No More!”, firing off Tweets, text messages, phone calls and e-mails to tens of thousands of people.

Across from Odom is Steve Foley, a 37-year-old, laid-off mortgage manager who writes the conservative blog, “The Minority Report.” On a wall is a whiteboard with a list of U.S. House and Senate races they’re targeting. Incumbents’ names are scribbled in pink, and almost all, save for McCain, are Democrats.

Together, Odom and Foley sometimes make hundreds of calls in a day to draw folks out to local meetings to talk about working to get others involved. Or they’ll fly to Philadelphia to hold training sessions to teach grassroots activists how to write press releases, use social media to strengthen the cause and organize networks to get out the vote.

After dispatching a flurry of fundraising e-mails on behalf of Charles Djou in Hawaii, Odom and Liberty First had enough money to buy radio ads and pay bloggers to help Djou become the first Republican in nearly 20 years to win a congressional seat from his state. Odom and Foley also went to Honolulu for a week to pitch in for the campaign.

For Odom, it’s not just about 2010. He’s enlisting statewide coordinators in places like Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Illinois and New Hampshire in the hope that they will convince others at the county and precinct level to take up the cause so, by 2012, enough activists are in place to make a difference.

“This is very long-term for us,” says Odom. “What is our ultimate goal? To make sure that we’re represented by people who are looking out for our rights and upholding the Constitution. … And, if they don’t, to make sure we have infrastructure to really take them out rather than have these thugs that are in there for 30, 40 years.”

Yucca Valley, a desert town of about 20,000, survives because of the places surrounding it, the people they draw and the trickle-down jobs they create. There are new installations going up at the Marine base in nearby Twentynine Palms; Joshua Tree National Park, and the visitors it brings to grocery stores and restaurants; houses that went up over the years for retirees and those who live in Yucca Valley but work elsewhere.

Bill Warner came to this place as a young man of 26, with his wife, Pat, and a 9-month-old daughter. Fresh out of the Navy, he went to work for a civil engineering firm, purchased a house on the GI bill and then bought the engineering business and made it his own, expanding from a two-person operation (Warner and his wife) into a solid venture with 55 employees.

A pull-yourself-up-by-the-bootstraps capitalist, he rode the ups and downs of his community, helping build the Walmart center and so many other enterprises. And he saw business dip when the recession hit.

Warner now sees the life he’s built and the future of his daughter and grandson being threatened by “tax-and-spend” leaders who can’t do as he has always believed: Live within your means.

But it’s not just about his individual situation, or his family’s. As he said that day in Searchlight: “I’m concerned about the ability of the country to survive.”

He reminisces about better times growing up in Orange County during the ’50s, the son of a bricklayer and a housewife. Those were days filled with camping and fishing, swimming in the Salton Sea (too polluted now for that, Warner laments). But they were also times, in his view, of less “political strife.”

“We certainly didn’t have the taxes, and the government didn’t have the debt that it’s incurring today. What I see, and I think a lot of people see, are the risks of that debt and the nonsustainable parts of our politics and the economics really putting at risk our way of life.”

Having lived all his life in California — today, the most debt-ridden state in the nation — Warner has seen firsthand the damage severe budget deficits can do. He’s experienced the tax hikes and cuts to services, and now he fears the federal government is following in his home state’s footsteps.

And, so, he took his motorhome to Searchlight to show his concern. And when the mayor of Yucca Valley called earlier this year, proposing they launch a Lincoln Club to help raise money to support conservative candidates, Warner didn’t hesitate. He helped recruit other board members, mailed out fliers for their first meeting in April and, at that $50-a-head luncheon, stood before the 80 or so souls who showed up and tried to explain what his club hoped to do:

“It takes action. We can all complain to each other, but we’ve got to act on our feelings.”

The board now meets in the snug conference room of the local State Farm Insurance office, owned by board member Bob Dunn. Besides Warner, Dunn and the mayor, a 33-year-old self-described “politico” who once interned for former Sen. John Ashcroft, the board also comprises a bank vice president, a former mayor of Twentynine Palms, a school board trustee and an optometrist.

A few weeks ago, five of the seven gathered for their regular board meeting and soon were engaged in a lively discussion about California’s budget crisis, Arizona’s new immigration law and the overall state of the union.

“Do you want to see why people are upset?” asked the bank VP, Paul Hoffman. In response, he held up his cell phone to show off a picture making the rounds in viral e-mails. It’s of a sign supposedly erected somewhere in Pennsylvania that reads: “So now we know” and goes on to say: “‘Change’ (equals) More Debt, More Taxes, More Welfare, More Regulation, More Government, More Wasteful spending, MORE CORRUPTION. Thanks Mr. President.”

Hoffman snickers, and without missing a beat mentions another e-mail about a sailor who took offense to a letter to the editor that accused the federal government of “spending money like a drunken sailor.” Hoffman tells the group the sailor sent back a reply, saying: “The difference is a drunken sailor, when he runs out of money, he quits drinking.”

As the chuckles subside, Warner begins handing out roast beef and turkey sandwiches and the group gets down to business. They have endorsements to review for California races, campaign contributions to consider, recruitment.

They want, quite simply, to keep acting in their own way on the anger they feel.

To do, as Warner likes to say, what they can do.

Pauline Arrillaga is an Associated Press national writer, based in Phoenix. She can be reached at features(at)ap.org.

Tags: Arizona, Barack Obama, Beverages, Bullhead City, Business And Professional Services, California, Chicago, Colorado, Facebook, Food And Drink, Illinois, John Kerry, Las Vegas, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, New York City, North America, Political Action Committees, Political Endorsements, Political Organizations, Protests And Demonstrations, Reno, Restaurants, Sarah palin, Senate Elections, Sports, United States, Women's Sports, Yucca Valley