Car plant a rare win for poor Indian farmers as battles rage with industry over land use

By Erika Kinetz, APSaturday, July 10, 2010

Land wars bedevil India’s rush to industrialize

SANAND, India — It doesn’t look like he’s won much from industrialization. Take his face, weathered beyond his 30 years, or the earth stuck to his bare ungainly feet.

Jaisar Khan Pathan, one in a long line of farmers, is simply too scrawny.

But Pathan, and scores like him who live in the shadow of a new factory built by Tata Motors to make its ultra-cheap Nano car, are the beneficiaries of the race to transform India from a nation of small farmers to an industrialized power.

They are part of a tectonic shift as millions move off the land into an uncertain future, even as others wage land battles that have blocked some of the world’s most powerful companies from building power plants, mines and factories.

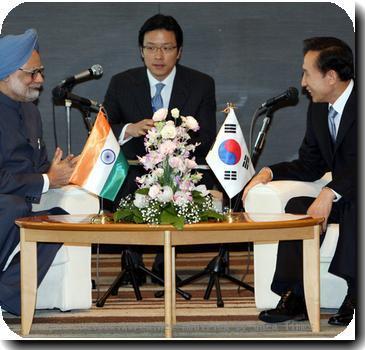

The conflict over land has fueled a violent Maoist insurgency across much of India’s least developed regions. The insurgency, which Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has called India’s top internal security threat, claimed 908 lives in 2009 and rebels were blamed for a May train derailment that killed 145 more.

Some say India is trying to industrialize too fast, without the education and infrastructure in place to give the rural poor a fighting chance.

“How long did the industrial revolution take to be implemented in the West? Two hundred years. You want to replicate the same model and squeeze it into 20 years. That’s not possible. The fallout will be massive,” said Bhaskar Goswami, an economist at the Forum for Biotechnology and Food Security in New Delhi.

Against this backdrop of strife, Pathan’s story is the ideal of what could be achieved if the more than 50 percent of Indians who live off the land get a real stake in the new economy. It’s a principle that advocates of market capitalism and human rights activists can agree on, but that often fails to materialize across rural India, where stories of powerful business interests and corrupt officials conspiring to throw poor farmers off their land are all too common.

Around the Tata plant in Sanand, in the western state of Gujarat, people have begun to talk of the “Nano effect.”

Go down a narrow lane that runs to dirt not 15 minutes from the factory and amid the gamboling goats of Chharodi village, you will find 25 new homes.

Property prices have risen sharply — from 50 to 400 percent — and men are making fortunes brokering land deals.

The village head says three dozen of the 3,000 people in Chharodi have gotten work from contractors. The Nano factory hasn’t given them jobs directly, but it has offered a toehold in the industrial economy. They remain farmers, but a growing part of their income comes from informal business ventures or work for contractors.

Pathan and his three brothers sold the government one-third of their family farm to make way for the Nano plant. They were paid 20 million rupees ($432,900) — a fortune even in Gujarat, one of India’s richest states.

Ask the Pathan brothers what they did with this money, and they grin like schoolboys.

They bought 2.7 hectares (6.6 acres) of land — more than doubling their initial landholding — three kilometers (two miles) away, where they are preparing to plant their first crop.

They bought seven tractors and three Bolero jeeps, which they use for contracting work at the Nano site, raking in 455,000 rupees ($9,848) a month.

They are rebuilding their family home. Gone is the mud and thatch. Today their angular concrete two-story is the biggest on the block.

“You’ve done a damn good job out here,” Pathan says of Ratan Tata, who heads the Tata group’s sprawling industrial empire.

The “Nano effect” can be attributed, in part, to the state’s scrupulous care in avoiding conflict with the high-profile project.

The Nano factory and adjacent vendor park sit on 445 hectares (1,100 acres), most of which belonged to a government agricultural university that used it for grazing and experimental farming. Just seven families sold off a portion of their holdings to make way for an access road. The value of the rest of their property skyrocketed after Tata Motors came to town.

Those who sold got a decent price and, living up to Gujarat’s renowned business savvy, demonstrated more entrepreneurial zeal and money management skills than the average subsistence farmer.

State officials also scuttled plans for a 177 square kilometer (68 square mile) industrial zone around the factory after locals protested. They now plan to put it on fallow land about 10 kilometers (six miles) away.

Elsewhere in India, powerful multinationals, including South Korean steel giant Posco, India’s Tata Steel, and U.K.-listed Vedanta Resources are all embroiled in land fights.

Violent farmer protests over land, led by opposition politicians, forced Tata Motors to move the Nano factory site from West Bengal state to Gujarat, delaying full-scale production by nearly two years.

Even business-friendly Gujarat is vulnerable to land fights. Farmers opposed to a cement plant they say cuts off a crucial irrigation pond complain of harassment by police and stone-throwing company goons. A proposed nuclear power plant has come up against opposition from locals who say it would displace 10,000 families. Others protest that a proposed special economic zone would destroy 3,000 hectares (7,400 acres) of mangrove trees, which protect the coastline and support a local fishing industry that employs 10,000 people.

Indian policymakers are trying to figure out how to broaden the “Nano effect” and help land losers across the country become stakeholders too. Critics say their failure so far to do so has dragged down India’s growth and left the mass of poor rural Indians with little to show for their nation’s progress.

Too often, farmers who sell their land to make way for industry quickly spend that money, then struggle to make a living with outdated skills.

“The compensation is usually for consumption. Within no time the money is used up,” said Nayan Raval, a top adviser to the Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation, which promotes business development. “Only a few enlightened farmers invest it.”

Biswajit Mohanty, a lands rights activist in the eastern state of Orissa, says that in poorer areas, land acquisition rules are twisted to accommodate business interests, usually mining conglomerates, which often force farmers to give up their land for a pittance.

“In most cases, the government does not follow the procedure, and village councils are manipulated or threatened to agree to sell land,” he said. Anger at the expropriations has helped the Maoist rebels recruit new cadres to fight the government.

Two proposed national laws, drafted in response to clashes over land acquisition, would introduce minimum protections for the displaced. Some states, including Gujarat, give farmers back a fraction of the land they’ve vacated after it has been upgraded with roads and electricity, or give preference to original land owners when allocating new industrial zones.

“Land is a finite resource,” said Arvind Agarwal, managing director of Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation. “Sixty percent of Gujaratis and 70 percent of the country depend on land. You have to meet their aspirations.”

But many say such measures can only help some people, some of the time.

Even industrialization’s staunchest advocates acknowledge that the transition out of agriculture — or for tens of millions of nomadic tribal people, a pre-agricultural lifestyle — typically takes generations.

Even in Sanand, few have made a direct leap from farm to factory without a helping hand.

Tata Motors, which declined comment for this article, says 95 percent of the factory’s 2,400 employees are locals, most trained at government technical institutes.

Gujarat officials enrolled 1,500 young people from surrounding villages in a skills training program it launched the same month the Nano deal was signed.

While the entrepreneurial skill of the Gujarati people and the state’s care with training and land acquisition surely contributed to the “Nano effect,” so too did infrastructure. Without roads and electricity — absent in swaths of India — the villagers of Chharodi would not be able to ply their new trades.

“People who lose their land have to be stakeholders,” said Swaminathan Aiyar, a columnist and fellow at the Cato Institute in Washington D.C. “All disruption has short term big disadvantages. The question is what happens in the long term. If there is infrastructure and electricity, there are so many opportunities.”

Just ask farmer Pathan.

“Bring more companies,” he says, grinning.

_____

Associated Press writer RK Misra contributed to this report.

Tags: Asia, Business And Professional Services, Energy, India, Manmohan Singh, Materials, Municipal Governments, Political Activism, Political Issues, Sanand, South Asia, Utilities