From bike lanes to wood chips, mayors from cities worldwide compare notes at climate talks

By Jan M. Olsen, APMonday, December 14, 2009

World’s mayors tackle climate change on their own

COPENHAGEN — It isn’t easy getting Italy’s city dwellers out of their Fiats, off their Vespa scooters and onto bicycles to ride to work, “like here in Copenhagen,” says an Italian environmental official.

“It isn’t a matter of painting a right lane and saying, ‘This is a bike lane,’” explained Emanuele Burgin, a Bologna provincial councilor. “We realize we’re far away from this.”

But Copenhagen’s lord mayor has her problems, too. Finding enough parking space for all those bikes is just the beginning.

“First, we must get rid of our coal plants, and we need to get that subway expansion built,” Ritt Bjerregaard told The Associated Press. She also wants even more Copenhageners cycling than the one-third who pedal each day to the office or school.

Bjerregaard and some 80 other mayors and local officials, including New York’s Michael Bloomberg and representatives of Tokyo, Jakarta, Toronto and Hong Kong, have converged on the Danish capital in their own climate and energy summit. They’ll compare notes on how cities can combat climate change and save money on energy and other costs.

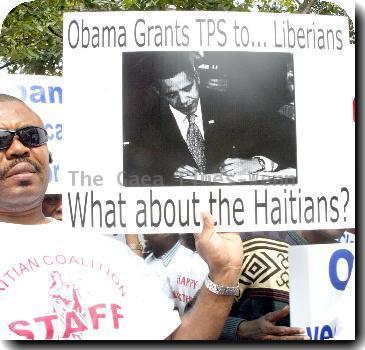

This five-day “cities summit,” opening Monday, will parallel the second week of the U.N. climate conference, intended to boost international efforts to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide and other gases blamed for global warming. President Barack Obama and more than 100 other national leaders will attend that U.N. conference in its final days.

Today’s cities and towns consume two-thirds of the world’s total primary energy and produce more than 70 percent of its energy-related carbon dioxide emissions, the International Energy Agency reports. That will grow to 76 percent by 2030, the agency says. Most comes from electrifying and heating private, commercial and municipal buildings.

In a report last week, the IEA’s executive director, Nabuo Tanaka, said local authorities “have significant potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions” through renewable energy and other means. “Yet relatively few are taking up the challenge,” he said.

Cities face many obstacles to becoming more “climate-friendly” — from extensive old infrastructure that would be cost too much replace, to political interests that resist City Hall’s plans. The New York example is illustrative.

New York City last week approved legislation requiring owners of larger buildings to conduct energy audits and replace insulation and take other steps toward energy efficiency. But under pressure from developers and real-estate interests, the measures were stripped of requirements for more costly improvements, such as total overhauls of heating systems and replacing windows.

Similarly, Bloomberg’s efforts to cut traffic in Manhattan by charging fees to drive cars in certain neighborhoods was blocked by New York State politicians.

London succeeded where New York failed. In 2003, then-Mayor Ken Livingstone introduced a daily “congestion charge” — the equivalent of $16 — on cars and trucks entering the central city during business hours.

Other big cities are also trying to lead on climate. Sao Paulo, Brazil, for example, a sprawl of 11 million people, has by law set as a goal a 30 percent reduction in emissions by 2013. It has already achieved 20 percent since 2005, chiefly through its new system of generating biogas for energy at landfills, instead of allowing waste methane, a greenhouse gas, to rise into the skies.

Here in this city of 1.2 million, Bjerregaard also has set ambitious goals.

Copenhagen reduced its CO2 emissions by 20 percent from 1995 to 2005. The lord mayor plans to reduce it by another 20 percent by 2015, and then to become “carbon-neutral,” free of fossil fuel for core needs, by 2025.

Wind turbines off this port city’s shores and on land now supply at least 13 percent of Copenhagen’s electricity, and at least 14 percent more comes from biofuels and waste incineration. Copenhagen has 190 miles (307 kilometers) of heavily used bicycle paths, and an excellent public transport system. It even offers urbanites “home visits” by climate consultants to help families become more energy-efficient.

Rows of scores of bicycles outside buildings are a common sight in this clean, modern city. Foreigners “laugh when they hear that bicycle parking also is a problem” Bjerregaard said.

To reach its ultimate goal, the city plans to switch power and heat generation fully from coal to biomass — specifically, wood chips, which are less than 2 percent as polluting as coal. Copenhagen’s unique “district heating system” — 97 percent of the city is linked to the waste heat generated by electricity plants — will make it easier to convert.

“In the United States, heating is seen as a private matter that’s up to individual citizens to decide,” Bjerregaard said. “Here in Denmark we operate with a common approach, a strong community mentality.”

She also is pushing completion of an important new line on Copenhagen’s elevated-and-underground Metro train system, opened only in 2002, and improvements in the convenient bus system.

“We are far behind when it comes to the Metro,” she said. As for the buses, “If we create these lines where they drive fast, and people can see how fast they drive, we can have more people take public transportation.”

Although Italians may not be filling up bicycle lanes, their municipal leaders sound intent on rolling back CO2 emissions, even if they’re starting late: Italy’s emissions have grown since it accepted the 1997 Kyoto Protocol climate deal, rather than declined as required.

Burgin, at a weekend briefing at the climate conference, said energy savings and conversion in the city of Milan alone could have met one-seventh of Kyoto’s demands on Italy. And he said Italian cities are fast catching up on controlling emissions.

“Climate change allows you to interpret your plans in terms of emissions. Until now everything we planned was planned in terms of money,” he said.

The city of Rome’s environmental chief, Paolo Giuntarelli, said his city intends to be the “first capital in Europe with an ambitious plan for energy self-sustainability.” Although Copenhagen may beat them to that distinction, the Romans have a serious motivation.

“We are bidding to host the 2020 Olympics,” Giuntarelli said, and Rome believes only a “green” city can snare that prize.

EDITOR’S NOTE — Find behind-the-scenes information, blog posts and discussion about the Copenhagen climate conference at www.facebook.com/theclimatepool, a Facebook page run by AP and an array of international news agencies. Follow coverage and blogging of the event on Twitter at: www.twitter.com/AP_ClimatePool

Tags: Barack Obama, Climate, Climate-cities, Copenhagen, Denmark, Energy, Energy And The Environment, Environmental Concerns, Europe, Italy, Municipal Governments, New York, New York City, North America, Transportation, Twitter, United States, Utilities, Western Europe